A Church in Doubt

Book Review by Richard Rex, First Things:

Book Review by Richard Rex, First Things:

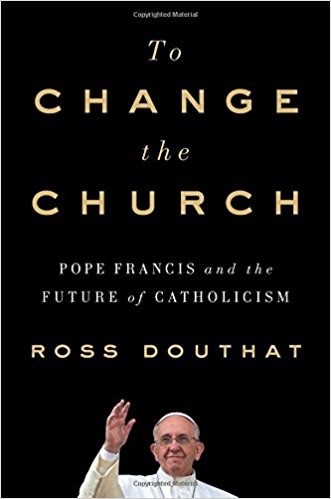

To Change the Church: Pope Francis and the Future of Catholicism by Ross Douthat

It is beyond question that the Roman Catholic Church is currently in the throes of one of the greatest crises in its two-millennium history. In human terms, its future might be said to be in doubt for the first time since the Reformation. The broad contours of the present crisis are the onward march of secularization in Europe and North America, the purging of Christians from the ancient heartlands of the Middle East, and the erosion of South American Catholicism by the missions of the Protestant and prosperity gospels. More specifically, the horrific and continuing revelations of the sexual and physical abuse of the vulnerable by the clergy, and of the failure of the institutional Church to identify and address the issue, have in some places turned a Catholic retreat into a rout. The dramatic and utterly unforeseen collapse of Catholicism in Ireland in little more than a generation, for example, harks back to the tectonic religious shifts of the early sixteenth century. Only in Africa is there much by way of good news, and it is not always clear how good that news is.

The crisis has come as a shock. No such prospect could have been in the mind of John XXIII in 1959 when he announced his plans for a Second Vatican Council. At that moment, the postwar triumph of liberal democracy in Western politics and of American Catholicism in the Church seemed to mark the final resolution of a dialectic that had dominated Western history since the French Revolution. For much of that era, a version of political liberalism that was often tempted to prefer freedom from religion to freedom of religion had regularly found itself in conflict with a resurgent and counterrevolutionary Roman Catholicism. The rise of totalitarianism, which was defeated in the form of Nazism but briefly triumphed in the form of Marxist Leninism, fostered the emergence of a politically liberal Catholicism that, in the aftermath of global conflict, produced the European project and Vatican II. As long as the Soviet Empire endured, Christianity and liberalism coexisted in a measure of harmony. It was an era in which popular images of the Catholic priesthood were shaped by Cardinal Mindszenty rather than Cardinal Law, by Don Camillo rather than Father Ted. John Paul II, socially conservative but politically liberal, symbolized this brief and, as it turned out, unstable synthesis. The rapid rise of social liberalism threatened this equilibrium, and with the end of the Cold War, signs could once more be seen of the return of a more resolutely anticlerical liberalism along nineteenth-century lines, though formulated in the new language of universal human rights. Social liberalism is founded upon a very different ethic from Christianity, and the increasing tension between these two bodies of doctrine is the cause of the contemporary crisis of Catholicism in the West.