Editorial Blog

Dave Doveton is the Senior Editor of this website. These articles are mostly concerned with authentic, biblically orthodox Christian faith and its interaction with the Anglican Church, especially the Church of England, and the wider culture. Please press the ‘Refresh’ or “reload’ button to ensure you see the latest blog post at the top of this column.

Possible outcomes after Lambeth 2022 – how should we pray?

By Andrew Symes, Anglican Mainstream:

It’s a risk saying anything about this Lambeth Conference, because any “news” being reported will have almost certainly been reported somewhere else first, and comment on the latest development risks being out of date as soon as its posted. This is why we have compiled a selection of articles about Lambeth (perhaps the most comprehensive available on the web!) which is being added to daily, and is proving very popular.

But the amount of information and opinion can be overwhelming – so here is my brief summary so far:

Any hope for the peaceful and unifying conference envisioned by the planners was disrupted when the leaders of the Global South grouping (GSFA) made it clear before arriving that the question of shared commitment to bible-based orthodoxy should not be set to one side at the Conference. This strong and well-organised stand was perhaps unexpected, given that the Gafcon-aligned ‘conservative hard-liners’ of Africa were not coming. Perhaps partly as a result of this GSFA lobbying, the organisers introduced a reference to Lambeth Resolution I:10 (1998) into the section of the “Calls” document relating to ‘Human Dignity”.

The commitment to heterosexual marriage, and welcoming pastoral care for same sex attracted people agreed in 1998 was referred to as “the mind of the Communion”. An immediate, furious reaction from bishops in North America and other Western provinces led to a second version, which described different views and practices relating to Resolution I:10, and concluded: “As Bishops we remain committed to listening and walking together to the maximum possible degree, despite our deep disagreement on these issues.”

Following this, the GSFA said they would seek to bring Lambeth I:10 to the Conference for re-affirmation, and that they would not receive Holy Communion with bishops who openly deny the Resolution in actions and words. While Archbishops Welby, Cottrell and others sought to encourage the bishops to put aside the differences for the sake of addressing serious problems in the world, the GSFA said that a broken church, with leaders who are not walking together, cannot heal a broken world.

As I write, GSFA have agreed not to try to force a debate and vote on I:10 in plenary, but are organising an opportunity for delegate bishops to affirm the resolution online, in such a way that numbers and regions will be recorded but not names. Meanwhile the Archbishop of Canterbury has reiterated the sentiment of the second draft of the “Call” on human dignity: Resolution I:10 is still there and is affirmed by the majority; others have come to different conclusions in their beliefs and practices; let’s be united on the “great issues” (implying thereby that issues of sexuality, marriage and the doctrine of the human person are, in Justin Welby’s view, ‘adiaphora’).

It is worth asking at this point, what is the endgame? What do the various factions hope to achieve? What outcome should we pray for?

On opposite ends of the spectrum, there are those who would like their view, on marriage and sexuality, on Scripture, the nature of salvation and the mission of the church, to be adopted by the whole Anglican Communion. From the orthodox point of view, this means that a strong commitment to biblical orthodoxy, based on the foundations of Anglican doctrine, would be restored to the Communion. From the perspective of those whose understanding of Christian faith corresponds more to a progressive worldview, this means replacing Lambeth I:10 with an unambiguous commitment to the LGBT agenda: acceptance of same sex marriage and secular-gnostic-progressive readings of Scripture. The problem is that as in 1998 and the aftermath, positions are entrenched, and there is no mechanism for enforcing adherence to any resolutions.

Not long ago, the second of these options (ie, revisionist ‘victory’) seemed more likely in the Western provinces – it was assumed in many quarters that by now the ‘arc of history’ would have converted most people to ‘get with the programme’. Pressure from secular Western culture has made it increasingly difficult to change the revisionist trajectory of churches which are part of that culture. In fact one could argue that the Church of England’s commitment to “radical inclusion” has involved a current de facto rejection of Lambeth I:10 in many Dioceses, even if canons and liturgies have technically not changed.

But this Lambeth Conference has given hints of a new reality. The secular world is not as interested in what’s going on in the church as in the past. Where the church was previously seen as another institution to be brought under the heel of the progressive agenda, it’s now seen as irrelevant. Previously, LGBT activists outside the church would promise their support for those trying to bring about change. Now as the church isn’t even on the radar, especially for young people, changing its policies seem less important – although this theory will be tested in full if there is a major debate in general Synod next February.

In the middle, there are those wanting to hold the Communion together through negotiation and compromise.

The preferred position of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Conference organisers seems to be to attempt to sideline debates on sexuality and wider understandings of theology, to see them as evidence of legitimate diversity to be overcome through “good disagreement” or whatever the current term is. Focus should be on what unites Anglicans – belief in God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit, shared identity as baptised Christians, a sense of concern and responsibility for the local community around the parish and a hope for global social justice.

This is the default situation in the Communion for many Anglicans. It can be referred to positively as a way of ensuring continued mission through preserving peace, and there is no doubt that getting bishops from all over the world in the same room to discuss serious issues facing the world as described in the ‘Lambeth Calls’ can have a positive effect. But it could also be seen as a policy of inertia, indefinitely postponing decisions on core beliefs and vision, and encouraging manipulation and compromise.

Then there is an increasing number, particularly in the Church of England, both on the liberal and conservative sides, who see that attempts either to win full ideological control of the Communion or to promote a false peace by airbrushing out irreconcilable differences will result in endless conflict and lack of progress in mission. The best solution is negotiated, organised separation. In the US, Methodists have formed two discrete denominations, one aligned with the global majority which is more conservative, and the other taking a more progressive stance. Congregations can choose which one to join. Could this be a model for Anglicans?

A proposal gathering support in the Church of England is the creation of a new non-geographical jurisdiction within the denomination. In both cases, both sides can retain their theological integrity and remain in the same denomination, without the need for conflict over buildings and other resources, and a degree of cooperation on projects of mutual interest can continue. It is institutional unity with built-in degrees of separation based around theology. In this scenario the conservatives in the Church of England would be aligned with global south conservatism, would retain control over liturgy, training for ministry, selection of bishops etc, would be free to get on with evangelism, but would also keep advantages of buildings and finances. There are obvious practical obstacles to achieving this: those committed to “total victory” and “priority of unity” in the C of E would not agree, nor would a Parliament and other influential institutions committed to LGBT rights (certainly not at present). Also, while some parishes might unanimously vote to join the new entity, in the majority of congregations such a suggestion would create more conflict and division.

So far we have not mentioned another option based on an emerging reality: informal re-alignment, involving a process of separation between the orthodox and the revisionists which is not sanctioned by Lambeth/Canterbury, but authorised and validated by a new centre of Anglicanism in the Global South. Already, Provinces representing a large proportion of the global Communion are not at Lambeth. Nigeria, Uganda and Rwanda, with a significant group from Kenya, feel that over the past 20 years the call for return to orthodoxy has been consistently rebuffed in favour of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s “walking together despite disagreements” approach. The Gafcon Jerusalem Declaration states: “We reject the authority of those churches and leaders who have denied the orthodox faith in word and deed.” In provinces whose leaders have consistently “denied the orthodox faith”, Gafcon Primates, while remaining part of the Anglican Communion have recognised new jurisdictions as authentically Anglican – such as ACNA, the Anglican Church of Brazil and the Anglican Network in Europe.

So how should we pray? Here are some key points:

- Increasing unity between Gafcon and GSFA and within these groupings, based around shared commitment to the biblical gospel, despite some differences over strategy.

- Stronger relationships between the orthodox in the global south (both Gafcon and GSFA) and biblically faithful Anglicans in the global north.

- Greater respect and cooperation between orthodox in the global north remaining in the Canterbury-aligned structures, particularly in the Church of England, and those in the new jurisdictions.

- Within the orthodox churches of the north, a developing posture of resistance-in-humility against false ideologies in church and culture, alongside evangelistic and pastoral zeal.

- Growth in the new Anglican jurisdictions.

- That leaders deceived by secular and gnostic counterfeits of Christianity, would repent and recover faith in apostolic teaching.

Our selection of articles (usually with two our three line summaries) from a wide variety of authors about the Lambeth Conference (perhaps the most comprehensive digest available on the web!) is being added to daily, and is proving very popular.

Persecution reveals a church’s true character

By Andrew Symes, Anglican Mainstream:

“People look at the outward appearance, but the Lord looks at the heart”. Most of us have heard this applied to us as individuals, but it is also true of the church. The most important aspect of the Christian life and the church is not optics, but interior health.

The early church at Pentecost looked wonderful, with prayer, generosity, successful evangelism and respect in the community. But its character was yet to be tested. The book of Acts shows the early church coming under severe pressure. Its first test of character was the change in how they were viewed by the authorities, from 2.47 to 4:3.

This is very relevant to Christians in the West. 50 years ago, most MP’s, doctors, lawyers and head teachers would have professed at least a nominal Christian faith. The Church had power, influence and respectability. Now the effect of decades of secularism is that most people in power are either indifferent to faith, or hostile to it.

Other churches around the world have been on the margins for years, even centuries. But for us it’s a relatively new place to be. What will be revealed about the character of our church when it faces persecution?

Acts 4: the pressure, the response, the principles:

Acts 3 tells the story of a severely disabled man who was healed miraculously by God through Peter and John. Peter preached the gospel of Jesus to an enthusiastic crowd which gathered. The religious authorities were angry that the apostles were talking about Jesus, blaming them for his death, and that the new Christian movement was growing in number. But it was more than that. The preaching of the gospel was not just calling people to believe in something or someone in their personal lives. It was an announcement of the reality of God’s reign which would challenge all human systems. Peter was not saying: “you might find it helpful personally to believe in Jesus”, but “look what has happened! The healing of the paralysed man reveals the true nature of reality, and proves the inauguration of the rightful authority which you have been ignoring!”

The religious authorities tried to suppress the movement by arresting the leaders, interrogating them and beating them. Peter and John were not intimidated, but calmly refused to stop speaking about Jesus. However, this was a real threat to the new church. A conflict had been set up. The followers of Jesus were now enemies of the religious establishment, who only a few weeks before had successfully petitioned for the use of Roman power to put Jesus to death. This wasn’t just being unpopular – there was threat of imprisonment and possibly death.

The response of the church, and its underlying guiding principles, can be seen in Acts 4:23-31.

First, we see the whole church taking responsibility. Peter and John didn’t just get together with an inner circle of leaders to decide what to do. They reported to the whole church what had happened. There was an assumption that the church is the community of faithful people, a body, not a structure and its leadership which people attend as spectators.

Second, we see the church praying as a first response. Sadly, and I include myself here, this is not the natural reaction for many church leaders influenced by secularism. When faced with a crisis, especially opposition like this, the first response is too often to panic, alone. And then maybe to think about solving the problem – can we raise money? Can we go away to a safer place? Can we give in to the demands of those who are attacking us, to make peace? But that’s not what happened here. You don’t see a leader panicking alone and making plans. You see leaders telling the church about the problem, and then the church prays!

Third, we can learn a lot from the underlying assumptions behind the prayer. As they turn to God, they begin by recognising that he is the creator of all things, and he is in charge of the situation. It sounds obvious but it’s amazing how Christian leaders can doubt these basic facts. At the start of the Covid pandemic, a well-known theologian wrote articles published in major outlets like Time Magazine as well as Christian websites, saying that God laments with us in our suffering, but was not responsible for the pandemic and had no control over it. I think he wanted to dispel the caricature of an angry, cruel God “smiting” people – but in doing so he denied that God is in charge. But when in Acts the Christians prayed “sovereign Lord” that is the first thing they affirmed, even in the face of a major threat when doubts might come in about whether God can help us. For them, we can trust that God is in control of everything, because he made everything.

In their prayer they then turn to Scripture. In a few words they express what they believe about the bible, the ancient words written over hundreds of years which were part of their faith background. God spoke those words, by the Holy Spirit, through the human author. Acts 4:25 is a wonderful, short clear summary of the doctrine of the authority and inspiration of Scripture. They select a (presumably memorised) text which is relevant to their need. We’ll come back to Psalm 2 later.

In their prayer they outlined the problem to God, not because he didn’t know their need, but for them to be clear in their own minds what the issue was that they were praying about.

- They were realistic. A common misconception among some Christians is that it’s negative to focus on the problem. But here, there is a recognition of dangerous opposition from human forces – Jewish leaders and Roman authorities – which on the face of it seems too strong. How can the church survive in the face of this?

- But in their analysis of the problem, they weren’t primarily concerned about threats to their own safety or to blocks on the growth of their organisation. They saw the opposition as a continuation of the terrible scandal of opposition to God and to his anointed Son Jesus. The world trying to block out Jesus instead of giving him glory was, and is, and outrage.

- They affirmed again that God is still in charge of the whole process – he had permitted even the crucifixion of Jesus as part of his plan.

- Then they brought their request. They did not pray: “Lord help us to be winsome and not get into trouble again”. Instead, they asked God to “consider their threats”. They drew attention to the persecution in an appeal for justice.

- Then they prayed for boldness in evangelism, and miracles in Jesus’ name.

Their prayers were based on their understanding of reality shown in Psalm 2.

The secular view is that this world is all there is. There is no spiritual realm. Human society faces problems which can be explained in human terms. Maybe it’s because of class struggle, the oppressor against the oppressed. Or maybe it’s because individuals and markets are not free enough, or taxes are not low enough! or because of ignorance, or mental health, or lack of science and technological solutions.

Here in Psalm 2 there is another explanation, a spiritual and moral one. The natural orientation of human beings is to rebel against God and his anointed Son and King Jesus, trying to throw off God’s authority and establish our own, whether as individuals or as small and large groups.

The Psalm makes it clear that God is not just the local God of Israel, but the God of the whole world. His plan is to establish Jesus as King among his people, from where his authority will extend throughout the world. “I will make the nations your inheritance”, says the Father to Jesus. The call to rebellious human beings is to turn their attitude around, to recognise God’s authority and serve him, to “kiss the Son” which means to worship Jesus.

If this is God’s ultimate vision, then it was clear to the apostles and the early church what their role was. They had just seen Jesus rise from the dead and ascend to heaven. Their role was to tell everyone about this, not in their own clever ability with communication or impressive credentials, but with God’s power that would be shown in miracles. So they prayed, simply, “God help us to do this”.

The choice for our church: compromise, pietism, or mission-in-persecution:

This “priority of evangelism” does not mean that Christians should ignore the cultural context in which they live, withdraw from the mandate to challenge false and harmful ideologies, work to change unjust structures, and offer practical relief to the suffering. It does not mean using ‘commitment to evangelism’ as an excuse to submit to and go along with lies and injustice in order to avoid persecution. It does not mean, for example, that a school with a Christian foundation should justify displays of a rainbow flag and other symbols of secular ‘progressive’ ideology, with the excuse that “evangelism” (redefined and narrowed down to a private message of personal salvation) is still taking place.

Rather it means responding to opposition by praying on the basis of what the bible teaches, asking for prayer to share the message of the cosmic Lordship of Jesus, with power, and doing it boldly. The best examples of this today are found in the global south where the church is facing severe persecution, especially in China, Iran and northern Nigeria. If the church in the West wants to move away from compromise or pietistic irrelevance, and more towards the model of the early church, it needs to learn humbly from the church in the south.

[This is an edited text of a sermon preached on 24th July in Oxford].

See also: How to Pray in Opposition – Acts 4: A Model Prayer for Facing Persecution, by Kees Van Kralingen, The Gospel Coalition

Lambeth Conference: “Human Dignity” call to be revised

By Andrew Symes, Anglican Mainstream:

The Study Guide for the Lambeth Conference sets out the ten areas for discussion and the draft “calls” which the bishops are being asked to endorse. Following its publication, many bishops from the global north and other supporters of a more progressive interpretation of Christian faith, have made their objections clear.

The ‘Human Dignity’ section includes this paragraph:

“Prejudice on the basis of gender or sexuality threatens human dignity. Given Anglican polity, and especially the autonomy of Provinces, there is disagreement and a plurality of views on the relationship between human dignity and human sexuality. Yet, we experience the safeguarding of dignity in deepening dialogue. It is the mind of the Anglican Communion as a whole that same gender marriage is not permissible. Lambeth Resolution I.10 (1998) states that the “legitimizing or blessing of same sex unions” cannot be advised. It is the mind of the Communion to uphold “faithfulness in marriage between a man and a woman in lifelong union” (I.10, 1998). It is also the mind of the Communion that “all baptized, believing and faithful persons, regardless of sexual orientation are full members of the Body of Christ” and to be welcomed, cared for, and treated with respect (I.10, 1998).”

The offending sentences (highlighted in italics above) were initially defended by Lambeth spokesmen as simply stating fact, that a resolution was passed which while not being legally enforceable, nevertheless indicates the view of the overwhelming majority of the Communion. However, those objecting (a selection can be found here) clearly view Resolution I:10 as a dead letter, which according to C of E bishops is now on the negotiating table in the Living in Love and Faith discussion process, and according to Welsh, Scottish and north American bishops, is an example of “prejudice that continues to threaten human dignity”. They argue that Lambeth I:10 is an embarrassing legacy of past history and should simply not be referred to at all, in the interests of “reconciliation”.

In a message to his Diocese, the Bishop of Oxford says:

“It will be an immense privilege to be present at the conference and to hear so many different stories. We are aware as we travel to Lambeth of the pain and hurt of many LGBTQI+ people and their families in advance of the conference, and the painful divisions in the Communion around issues of human sexuality. We welcome the announcement yesterday (see below) that there will be changes made to the draft Call on Human Dignity. We pray that every interaction around these issues will be marked by grace and love.”

He says that the Lambeth Conference is “An opportunity to listen to one another as Christians, sometimes across deeply-held differences”, and explains: “The ten Lambeth Calls were published for the first time on 20 July. The bishops leading the Living in Love and Faith ‘next steps’ group spotted an immediate challenge.

He goes on to quote:

“The Church of England is just one voice among 41 member churches of the Anglican Communion. However, it has within it some of the conflicts and disagreements surrounding questions of identity and sexuality that influence the Communion’s discussions and deliberations about these matters and which the Human Dignity Call acknowledges.

That is why, in the Church of England, the Call’s affirmation of the Lambeth Resolution 1.10 (1988), that same sex unions cannot be legitimised or blessed, will be deeply troubling and painful for some whilst offering welcome reassurance to others. It is important, therefore, that the Call also affirms the safeguarding of human dignity through deepening dialogue about profound disagreements.

It is within this spirit – of respecting the dignity of every human being by creating space for dialogue – that Living in Love and Faith (LLF) continues its path towards discernment and decision-making regarding questions of identity, sexuality and marriage.”

Bishop Steven concludes:

“The group in charge of co-ordinating the Lambeth Calls met ++Justin yesterday to discuss the many concerns that had been raised, and it has been confirmed that the drafting group for the Call on Human Dignity will make some revisions and that the new text will be released as soon as it is available.

In October 2018, the bishops of the Diocese of Oxford issued Clothe Yourselves with Love, a pastoral letter that set clear expectations of inclusion and respect towards LGBTI+ people, their families and friends. Underpinning their letter was the foundational principle that all people are welcome in God’s Church; everyone has a place at the table.

We pray that the Lambeth Conference will be a time for deep engagement and movement on each of the ten Calls. Come Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of your faithful and kindle in them the fire of your love.”

Editorial comment:

The document Clothe Yourselves with Love, referred to above, led to nearly 100 clergy and lay leaders in Oxford Diocese signing a letter of complaint to the bishop, and set at least three clergy on the path to leaving the Church of England.

Anglican Mainstream commentary warned at the time that while the Oxford bishops were not openly advocating a change to the official teaching of the church, they were suggesting that it should be kept in the background as it is hurtful to LGBT people, to whose “full inclusion” the bishops are committed. In other words, treat ethical Christian teaching as a dead letter to be ignored when it conflicts with the embrace of the contemporary zeitgeist.

Those drawing up the text of the Lambeth Calls would have given it a great deal of careful consideration. One of the factors would have been the desire to listen to the majority world, the global south bishops who are attending and who want Lambeth Resolution I:10 affirmed; another would have been making a clear statement about the dignity and inclusion of those who identify as LGBT. It looks like the organisers will bow to pressure from the progressive lobby straight away, and remove any reference to Lambeth I:10 and the biblical, historic understanding of sex and marriage from the final document. If tweets from the powerful can have this much effect now, what will be the chance of any reference to a conservative view of sex and marriage being part of any official statements and policy following the conclusion of the LLF process in the Church of England, to be brought before General Synod next year?

See also: Our full collection of news and comment on the Lambeth Conference

Canterbury rebuke to African Primates reveals theological difference and personal animosity

By Andrew Symes, Anglican Mainstream:

The public slap-down of the Primates of Nigeria, Rwanda and Uganda by the Archbishop of Canterbury (press release here, open letter here ) will not do anything to heal the long-running rift or promote the kind of unity that the final paragraph of the letter calls for. It will be viewed by the African leaders as another example of imperialism. The letter from Justin Welby attempts to correct what it sees as false claims while criticising those who say they will not attend the Lambeth Conference, but in doing so only reveals the gulf of worldview between the two sides. Some of the points that are made need further scrutiny.

Comparing the current long running debate on sexuality to the apostolic conference, reported in Acts 15, on admission of gentiles to the church, is specious for a number of reasons. First, that conference came to a united decision, and did not allow the formation of two opposing views in the church as Anglicans have done with sexuality issues. The pro- and anti-gentile factions did not agree to “walk together” with differences on this key topic unresolved. Second, the answer to the problem in Acts 15 was decided by Scripture and agreement on its interpretation – here the Archbishop of Canterbury appeals to Scripture but does not address the fact that its teaching is being blatantly disregarded by leaders in the Western church. Third, one of the conclusions of Acts 15 was that gentile Christians should abstain from sexual immorality -(the parameters of which every Jew and proselyte would have understood clearly) – whereas the Western church appears to see this as unimportant or open to different interpretations.

Archbishop Welby’s letter mentions Lambeth I:10, and says it has not been rescinded. But the implication is that this resolution is of merely academic and historic interest, not morally binding in any way. This is why Provinces which have disregarded its teaching on sex and marriage still take part in the Anglican Communion as if nothing has happened. The disunity in the Communion, the “torn fabric”, has been caused by this arrogant refusal by Western Provinces to obey the mind of the Communion since 1998, not by the current boycott of Lambeth by African Provinces which is its consequence.

There is also a pointed reference to the clause urging compassion for “homosexual people”. The African Anglicans have not done very well on this aspect of Lambeth I:10, the letter implies, so they should not criticise those who are liberal on sexuality and marriage. Is Archbishop Welby suggesting a tit-for-tat, where the Western church is free to officially and liturgically bless gay marriage as long as some African Anglicans are unkind to gay people? Is this how the church should operate, where I justify my own sin and disobedience on the basis of another’s faults being as bad as mine?

There has been a lot of talk about sexuality between conservatives and liberals over the past decades. It suits those who hold the power, who follow the views of the secular West, to accuse less powerful conservatives of not listening, of losing their opportunity to put forward their viewpoint, when in fact the conservatives have listened enough; they do not agree; their re-statement of their own view, patiently again and again has not been heard, they feel that remaining at the table leaves them open to manipulation.

Then, astonishingly, the Archbishop of Canterbury accuses the Africans of not caring enough about poverty and conflict in their own countries; he lectures them on the dangers of climate change and “matters of life and death”, as if somehow he knows more about this and cares more than them. What is going on here? It seems that the Primates of Nigeria, Rwanda and Uganda had said in an earlier letter that the upcoming Lambeth Conference programme was focussing on ‘peripheral’ issues rather than the bible and the gospel. Of course they did not mean that physical suffering is unimportant and that the church’s role is purely ‘spiritual’ – the African and biblical worldviews do not make these dualistic distinctions. They were rather warning that a gathering of church leaders to agree unanimously on something patently uncontroversial – the need to tackle poverty and the effects of climate change – would be of little value without more profound agreement on the spiritual needs of the world and the solution in repentance from sin and faith in Christ. The sexuality debate shows that there is no agreement on this, and therefore no real basis for fellowship.

Ministry to the poor and suffering, which the churches of Nigeria Rwanda and Uganda do all the time, proceeds from their belief in the biblical gospel, not as virtue-signalling to a sceptical secular world. On the day that the Archbishop of Canterbury sent his letter of rebuke, Nigerian Christians were reeling from the latest atrocity, this time an attack on a church leaving dozens dead and seriously injured.

Lastly, the Archbishop of Canterbury insists that the Church of England has not changed its teaching on marriage or the place of sexual relations. Perhaps not yet, technically and legally, in the sense of changing canons and liturgy to permit the blessing of same sex relationships in church. But as this website has recorded over a number of years, in practice the teaching has changed on the ground and is in the process of being changed officially. Archbishop Welby’s “radical inclusion” speech following GS2055 (2017), the Living in Love and Faith process (2020-2022), and various bishops’ charges and Synod resolutions, declare again and again that since there is no consensus on the theological basis of the current teaching, and because of increasing critiques of that teaching from the culture being an obstacle to mission, the teaching can and should be changed when there is sufficient consensus. Meanwhile Bishops openly advocate for change (including the current Archbishop of York), and quietly permit informal breaching of the teaching at local level. Clergy and senior administrators are appointed whose lifestyle is openly at odds with the official teaching. And most recently, Bishops have been in support of an extreme form of a ban on ‘conversion therapy’ which would effectively lead to the criminalisation of those who base their pastoral care on the church’s official teaching.

So when, some time within 24 months after Lambeth, teaching, liturgy and canons do change to accommodate to the spirit of the age, it will be another line crossed in the long process and trajectory of revisionism, not a sudden switch from orthodoxy to heresy. It will further entrench the division between the institutions of the Anglican Communion Office and Western Anglicanism on one hand, and the vibrant Christianity of the global south on the other – a division which will be expressed in the non-attendance of certain Provinces at Lambeth.

See also:

Exclusion of same-sex spouses at Lambeth Conference ‘unfortunate,’ primate says, by Matt Puddister, Anglican Journal

Global South Revolts Against Western Sexual Agenda at World Health Assembly, by Stefano Gennarini JD, C-Fam: Only 61 out of 194 countries voted in favor of a new strategy of the World Health Organization to combat HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases, because it promotes the homosexual/trans agenda and sexual autonomy for children.

Pentecost: the descent of truth

By Andrew Symes, Anglican Mainstream:

Jesus predicted many times that the Holy Spirit would come after his death, resurrection and ascension. In John 16:13 we see one of those prophecies:

When he, the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all truth.

What did that mean? What kind of truth will the Holy Spirit guide us into? What is truth anyway?

There are several ways that truth is understood or defined today. The first says truth is objective, it can be calculated and measured, it is the realm of scientific facts, historical facts, evidence, reason, logic. Truth is not to be clouded by feelings or opinions. So, if I say 1+1=2, that is truth. If I say that these flowers are beautiful, or Jesus is Lord, those are personal feelings and opinions. I can only be sure of facts, so what I need is more knowledge. The way to solve the world’s problems and my problems is more education, better technology.

Another approach says truth is much more subjective. We construct our own truth from our feelings and the situations we find ourselves in. How you feel about something may be more important, more relevant and therefore more “true” that a so-called “fact”. So, 1+1=2 can be truth, Buddha is Lord can be truth, “I am born in the wrong body” – if its true for you, its true! Carl Trueman and others have shown that this understanding of truth is closely connected to our sense of identity; my “lived experience’ defining who I really am, a unique individual to be constantly “expressed”.

There is a third approach, which is to discover truth democratically, ie by majority opinion, often swayed by influencers. A wise voice of truth is not heard if not trending on social media. Conversely, by this measure, believing the “wrong” truth, the idea not approved by the “Party” or the elite formers of majority opinion, may be dangerous and should be suppressed.

Which one is the truth that Jesus was speaking about when he said “the Holy Spirit will lead you into all truth”? Is he talking about truth as in scientifically proven facts? Or as in a certainty of feeling with endless options? Or “everyone is saying it – therefore it’s self-evidently true – other views are harmful and should be banned”.

It’s none of these of course. Truth originates in the trinitarian God. Jesus did not merely claim to be a teacher of truth, but he said “I am the truth”. So to know the truth is first an encounter with the source of truth, an encounter which is life-changing. But it goes deeper than that. The disciples encountered Jesus as Truth when he was on earth, but he was another person, separate from them, and he left them. At Pentecost, Truth descended: the Spirit of God returned and actually entered the lives of the disciples – a more profound experience of the truth than seeing Jesus face to face. After Pentecost, in the book of Acts, we are told of people “receiving” the Holy Spirit and indeed in the Gospel of John, it says in chapter one that those who believe in Jesus and receive him will be counted as children of God. In other words, truth is nothing less than the experience of “Christ in you, the hope of glory”.

Then there is the factual, cognitive aspect of truth. To know the truth is to be gripped with wonder about God’s character and his actions. So on the day of Pentecost when people were filled with the Spirit they “declared the wonders of God” in different languages. And afterwards, when people gathered round to see what was going on, Peter preached, beginning, “Let me explain this to you – listen carefully to what I say”. Yes there was emotion, and experience, but Peter wanted to ground it in facts that we grasp with our minds. The truth is contained in a message – the fact that human beings are sinners and rebelled against God, but God sent his Son to die and to rise again to forgive sin and to reconcile people to God, and that’s what we find in Peter’s sermon. The Holy Spirit was guiding the people into truth through the sermon of Peter as well as through the tangible experience of God in their midst.

And so thirdly, truth is right action. The Holy Spirit enabled those who received him to do God’s will. Jesus said just before his ascension “when the Spirit comes, you will be my witnesses” and so truth is not just experience and knowledge but action in the world. The Holy Spirit gave a sign of this when he enabled the believers to talk in different languages, and the people visiting Jerusalem from different parts of the world understood them, showing that God’s intention was that eventually his message would be taken to all corners of the globe. And if we follow the book of Acts, it tells us the story of the Holy Spirit guiding the apostles in their mission to Jerusalem, Samaria and the ends of the earth, promoting the growth of the Kingdom of God.

The “truth-in-action” of the Holy Spirit is also seen in the behaviour of Christians in their local communities. Just a few verses at the end of Acts 2 gives us a flavour of what was happening in the early church. Miracles, love, fellowship, prayer, sharing of resources. This is the truth that the Holy Spirit was guiding his people into – truth experienced, truth known and truth that can be seen in changed behaviour.

So that was the early church on the day of Pentecost. What about us?

Firstly, what about the truth of our experience of God? While being thrilled by grasping the facts of the gospel and understanding what God has done for us is a work of the Holy Spirit, knowledge about God, or doing good works for him, is not necessarily the same as a life-changing and ongoing encounter with him. As the church continues to be made aware of dreadful failings of those leaders respected for their head knowledge of the bible, we realise the danger of hearts puffed up with knowledge and power being hardened to the Holy Spirit, the Lord, who proceeds from the Father and the Son.

Secondly, is our experience grounded in the truth of the revealed word? One of the causes of crisis in the Anglican Communion and other mainline denominations, is that the fake “truth” of the experience of the untrammelled self is now the majority opinion, which trumps what God has clearly said, and even trumps what science clearly demonstrates in some cases. The Holy Spirit does not lead the church into “new truth”, cancelling the teaching of the prophets and apostles. Rather he convicts and applies what is eternally true, for us today. In addition, he calls the church to teach and demonstrate the truth, and resist error – not to make a virtue of trying to accommodate truth and falsehood with each other!

Thirdly, when we know the truth, the Holy Spirit reveals truth to the world through our actions. Those disciples were slow, ignorant, and fearful, but after the coming of the Holy Spirit, they were on the ball, witnessing, organising, performing miracles. And so today, the Holy Spirit brings about transformation in the same way- here and here are two recent examples of how people can be supernaturally helped to move from a false self-understanding and wrong, destructive behaviour, to life in its fullness. People find new purpose in life. As the Spirit guides his people into truth they become united, they care for each other, they have an outward focus, on mission.

O thou who camest from above, that pure celestial fire to impart, Kindle a flame of purest love on the mean altar of my heart.

(Charles Wesley)

So Spirit come! put strength in every stride,

Give grace for every hurdle.

That we may run with faith to win the prize

Of a servant good and faithful.

(Keith Getty and Stuart Townend)

What are the main problems with contemporary secular culture, and why?

By Andrew Symes, Anglican Mainstream:

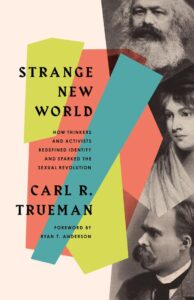

“In late 2020, while the world was on lockdown due to Covid-19, Carl Trueman published one of the most important books of the past several decades”. So begins Ryan Anderson in his foreword to Trueman’s latest book, “Strange New World: How thinkers and activists redefined identity and sparked the sexual revolution” (Crossway). While Anderson might be guilty of slight hyperbole, it’s certainly true that Trueman’s 2020 tome “The rise and triumph of the modern self” was very quickly seen as extremely important by conservatives seeking to understand the massive recent changes in the culture and worldview of the West. My feeling when reading Trueman was overwhelmingly one of relief – that at last someone was articulating soberly and clearly what the problem is. It wasn’t so much that it was new to me, but that his thesis confirmed and put together the fragments of ideas that I and others have been struggling to explain as we surveyed and chronicled the essential ideas of ‘progressivism’ or ‘woke’, and how they impact society and the church.

“Strange New World” (SNW) is not a summary of “Rise and Triumph”, but a more concise and accessible re-statement of the same main points:

- In the contemporary West, there has been a rapid and disruptive shift in how we see ourselves as human beings.

- The understanding of the self has moved from a subject-object, being an individual but existing within the constraints of a divinely-ordered creation and of community obligation, to a pure subject, in which my own feelings and desires define my identity and purpose; community rules and even biology can be seen as constraints on the authentic self.

- The self does not find authenticity in conforming, but in performing. So we have a culture of “expressive individualism”, which “holds that each person has a unique core of feeling and intuition that should unfold or be expressed if individuality is to be realised”, so therefore “authenticity is achieved by acting outwardly in accordance with one’s inward feelings” (SNW p22-23).

- The most obvious application of this is the sexual revolution. This is not simply a loosening of boundaries of sexual morality. It is seeing the self as largely defined by sexual preference and gender identity, so that the old moral boundaries are an existential threat to the expression of the newly liberated self.

- These new ideas did not suddenly emerge recently, but have been cooking for decades, even centuries, as Western culture has moved away from its Christian roots to a secular worldview. Delving into the history of the key ideas which have shaped this revolution helps us to understand more clearly what is happening, and what can be done about it by those who see the trajectory as hostile to Christian faith and destructive of human flourishing.

- So, having a basic grasp of the philosophies of Rousseau, Nietzsche, Marx, Freud and Reich is not just of academic interest. It sheds light on the assumptions of the majority in contemporary society in which we live, in relation to the nature of reality and the individual, how society should be run, where power resides, the combination of sexuality and politics in driving revolutionary change.

- Expressive individualism and Marxism have combined in a toxic mix, so that “two of the most unquestioned freedoms of Western liberal democracy, those of speech and religion, are now in serious jeopardy” (SNW p147). Anything which perpetuates the normativity of the old order must be suppressed and eliminated; this includes, of course, conservative Christianity.

- We are in a strange new world. “The last vestiges of a social imaginary shaped by Christianity are vanishing” (p169). Churches have been complicit in adapting theology and practice to the new thinking, rather than go through the costly process of critiquing it from a biblical perspective.

- The contemporary church needs to follow the example of the early church. Not by “warfare using the world’s rhetoric and weapons” (p177), but also not by being “passive quietists”, simply repeating messages that answer the questions of previous generations. Rather, recognising the spiritual battle, the church develops consciously Christian counter-culture of message, worship and community, offering an alternative, true vision of what it means to be human.

- “This is not a time for hopeless despair or naïve optimism. Yes, let us lament the ravages of the fall as they play out in the distinctive ways our generation has chosen. But let [this lead to] sharpening our identity as the people of God…” (p187).

All this in 200 pages means that Trueman’s new book is excellent, accessible to a wider audience than the much longer work, and a vital addition to the growing library on Christianity and culture, alongside, for example, Melvin Tinker and Sharon James. There is still a challenge for popular communicators to translate Trueman’s material into bite-sized chunks on video, and perhaps for churches and networks to incorporate some of its key insights into teaching material and statements of faith.

Other recent reviews can be read here:

How the self transformed sex, by Shane Morris, The Gospel Coalition

The best historical explanation of our current cultural crisis, by Jim Denison, DenisonForum

Strange New World, by Tim Challies

What are some of the immediate implications for Anglicanism? Trueman has shown that the problems of the 1970’s and 1980’s – growing acceptance of previously taboo sexual behaviours by radicals within the church, has become something different: the elevation and aggressive politicisation of the ‘authentic self’ based on ‘lived experience’, particularly sex and gender identity. This agenda has been supported by bishops and the church institutions in the West (for example, much of the text and video material in Living in Love and Faith assumes it), while evangelical and other orthodox leaders have often failed to sufficiently identify, analyse and resist it.

Those who accept Trueman’s thesis can be guilty of being over-pessimistic about the possibility of preserving a strong authentic Christian witness which can influence and change culture for the better, or perhaps too quick to withdraw from cultural engagement altogether. Others see the solution in tying church support too closely to partisan political leaders and programmes. But there are many Christians who, while retaining faith in bible-based doctrine and ethics, are not aware how much their thinking and practice has been shaped by secular thinking.

As Gavin Ashenden has recently pointed out, it has taken the courage of secular ‘prophets’ (he mentions Jordan Peterson and Douglas Murray) to raise the alarm, and to cause some church leaders to wake up and listen, when previously they were not paying attention to those in their own flock who have been making the same warnings for years. It may be that Carl Trueman’s books would have remained largely unread and unnoticed in the UK, were it not for high profile people outside the church (more: JK Rowling, The Times newspaper, Rod Liddle, Brendan O’Neill of Spiked, Kathleen Stock…) essentially saying we are entering an Orwellian dystopia: “this is not a drill”.

See also:

Lessons for the Church from the current transgender debate, by Jeremy Dover, Christian Today:

…our current cultural position of accepting “I am a woman trapped in a man’s body” is not the problem but just the symptom. Trueman says the true root of the issue is a “deeper revolution in what it means to be a self”.

Is “Be True to Yourself” Good Advice? by: Brian S. Rosner, Crossway

You don’t need to look far today to notice that personal identity is a do-it-yourself project.

CEEC releases new short films on sexuality

By Andrew Symes, Anglican Mainstream:

The Church of England Evangelical Council has launched a series of four short videos to help churches to engage biblically with issues around human sexuality. The first two films are available to view on YouTube: “God’s Beautiful Story”.

The first film addresses “silence” within many evangelical churches on the topic. Why is this? There may be anxiety about causing offence, lack of confidence in being able to articulate what the bible teaches, or fear resulting from hidden personal experiences. But meanwhile all the time, Christians are being encouraged to follow the messages of our culture, about the value and identity of self being defined by sex and gender.

These messages often amount to what are described as “lies”: “It’s really important to teach lay people the biblical perspective on sex and gender”, says one interviewee; “don’t be afraid to be a minority, a dissenting voice, speaking for truth”, says another.

The second film gives some initial pointers to how conversations might be started in church settings. Humility, an attitude of listening to real questions, fears and hurts, not placing burdens on people, and always seeking to be guided by the Spirit and to lead people to Christ are the recommended postures.

The next two instalments will address why issues of sex and marriage go to the heart of the Christian gospel, and therefore why they cannot be seen as ‘adiaphora’ (ie, things on which Christians can agree to differ). Lastly, there will be an introduction to the contentious matter of how radically differing understandings of the meaning of Scripture and what it means to be human can coexist within the same church. If changes are made to liturgy, doctrine or practice within the Church of England, might it lead to some kind of “differentiation”?

Many will appreciate the careful, gentle way in which these issues are raised, presented by relateable people rather than dry text. Churches will find the videos and the accompanying notes helpful in introducing discussions on sexuality and teaching the historic Christian understanding in a non-threatening way. It may be that there are some parishes where congregants and those on the fringe being drawn to faith in Christ are genuinely open to hearing, perhaps for the first time, what the bible teaches about what it means to be human, if it is presented winsomely.

Others will regard this initiative as “too little, too late”; many evangelical clergy are facing situations where congregations are already well-informed and bitterly divided on the issue. Church of England members, educated for years by secular culture, especially social media and the views and experiences of friends and family, have made up their minds and are not open to going back to what they see as outdated and untenable opinions. There are increasing numbers of parishes where clergy known to hold conservative views on sexuality are being told not to talk about them publicly; that they are potentially a “safeguarding risk” to “LGBT children”, for example (this has happened where parishes are connected to local Church of England schools).

These new CEEC videos show a diversity of different faces voices confidently articulating and commending a Christian sex ethic that is faithful to Scripture and the apostolic tradition, positive and attractive, and encouraging churches to do the same in the context of evangelism and pastoral ministry. That is a good thing.

The material would work best supplemented by material which explains the falsehoods of secular ideologies and why they have become dominant in the culture including among the leadership of the established church. It needs to be accompanied by a call to prayer and advocacy for continued freedom to teach and minister pastorally in the face of threats of harassment at work and even legal bans (eg on “conversion therapy”). And a reminder that, while disordered sexual desires affect all adults not just those with same sex attraction or gender confusion, these ‘minority orientations’ are not innate or always unchangeable: the Holy Spirit has power to enable a life of sacrificial obedience and holiness, but also transformation, as some have testified.

How can we start the conversation about sexuality in the local church? by Ian Paul, Psephizo [a more unequivocally positive review of the films – ed.]

What’s behind the bad news? Is there hope?

By Andrew Symes, Anglican Mainstream:

We’re entering a season where the church prepares to celebrate and communicate with confidence a message of hope. This was a challenge two years ago, when churches were closed for Easter at the start of the first lockdown, and nobody knew how much suffering the pandemic would bring. And yet, there seems to be even more of a disconnect between the narrative of the basis of our faith and the fear-inducing realities of the world around us now than there was then.

Today, multiple threats are all around us: a rapidly rising cost of living, unaffordable for many, at a time when governments are already heavily indebted. A war in Europe, a refugee crisis, and open talk of possible nuclear conflagration for the first time in more than 30 years. Climate change – what will that mean? And these are just effects on our physical environment. What about the spiritual vacuum of secularism, the largely unopposed invasion of anti-Christian ideologies, the turning to idolatries old and new even among the people of God?

The biblical writers addressed the big picture view of their contemporary culture as well as encouragements and direction for the local people of God. They connected the ongoing call to repentance and faith of individuals with the world, the past and future, and ultimate realities. We need to do the same, and this passage, 1 Peter 3:18-22, can help us.

For Christ also suffered once for sins, the righteous for the unrighteous, to bring you to God. He was put to death in the body but made alive in the Spirit. After being made alive, he went and made proclamation to the imprisoned spirits – to those who were disobedient long ago when God waited patiently in the days of Noah while the ark was being built. In it only a few people, eight in all, were saved through water, and this water symbolises baptism that now saves you also – not the removal of dirt from the body but the pledge of a clear conscience towards God. It saves you by the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who has gone into heaven and is at God’s right hand – with angels, authorities and powers in submission to him.

In the season of Lent the church traditionally reflects on temptation and sin. We recognise our negligence, weakness and our deliberate fault; our individual and corporate wrongdoings and also our sinful nature. But we also remember how Christ was human as we are, tempted and tested daily, but resisted sin and satan’s temptations. We look forward to celebrating on Good Friday the ultimate sacrifice and victory of the Cross, where as Peter says here, Christ died for sins, he died for sins that were not his own but our sins, he died in exchange for release from the judgement that our sins deserve. He died so that the curtain separating us from God could be torn open; he died not so we can make our own way to God but to do something impossible for us – to bring us to God.

Peter speaks about our sin, about the atoning death of Christ, and then he speaks about the resurrection. The ESV says “he was put to death in the body but made alive in the spirit” which is the more literal translation, but could imply that only his spirit was resurrected, not his body. The NIV has a capital S and so does the interpretation for us – it was by the Holy Spirit that he was bodily resurrected. Peter returns to the resurrection at the end of verse 21 – it is through the resurrection that our salvation, our new relationship with God, is assured and completed.

From resurrection he goes on to mention the ascension – Christ has gone into heaven and is at God’s right hand. So here in these few verses we have the gospel summarised: our sin; the cross and the resurrection of our Lord, our regeneration and baptism, the current position of the ascended Lord Jesus.

But then, what about these other bits in this passage? What do they mean and what is the relevance for us? Who are the “imprisoned spirits who were disobedient in the days of Noah”? How and what did Jesus proclaim to them?

A non-protestant interpretation is that the spirits in prison are Old Testament people in purgatory – Jesus preached to them between death and bodily resurrection. But this goes against the clear teaching of Scripture that we die once and then face judgement. Godly people in the OT received salvation by faith as a gift of grace while living, just as we do. There is no second chance in an intermediate state.

Some say maybe Peter is referring to the preincarnate Christ speaking to the people of Noah’s time through Noah. But Peter says Jesus went and proclaimed “after being made alive”, ie after his resurrection, not thousands of years earlier.

So, more likely, the “spirits” are the same as the “authorities and powers” that Peter mentions at the end of this passage. He is talking about the spiritual realm. We know from Genesis 6 that something not fully explained, but very bad happened just before the cultural sin and hardening of heart that led to the judgement of the flood. Spiritual powers at that time rebelled against God and acted directly on earth. They were placed under restriction – “in prison” as Peter says. Those same spirits still exist and have influence, as the bible teaches in other places. When Jesus ‘preached’ to them after the effects of his bodily death were reversed by God’s Spirit, this was an announcement to those principalities and powers, active but restricted from the days of Noah until now, of the victory and supremacy of the triune God over the powers of evil and hell.

Isn’t this a crucial perspective as we approach Easter and the season leading up to ascension and Pentecost?

Yes, the gospel is for individuals, of sins forgiven and empowerment for godly living.

But also, the gospel for the cosmos, of the sovereignty of Christ.

Looking at the world, we see the reality of evil. In our own hearts, yes, but as we look at incomprehensible brutality in Ukraine, or northern Nigeria, or Yemen, or at the state-supported mass killing of babies in the womb or widespread gender confusion among young people in Western culture, we see something horrifying, more to do with personal psychology than “the world”, more complex than the sins of individuals, not just the corporate dimension of “the flesh”. Evidence rather of the work of satan and the furious rebellious anger of the spiritual powers, held back from destroying all God has made and thwarting his plans. One day in the future these powers will be either destroyed, or fully, visibly submissive. But in the meantime, now, they have influence to cause disruption and agony on vast scale.

Knowing Christ’s victory displayed in his death and resurrection; knowing his status, gives us encouragement and hope, but not in a way that applies the gospel to church and individual spiritual life only. We are aware of the desperate needs of the world caused by evil, we face it, name it and analyse its effects as the biblical prophets did. Then we are motivated to engage in spiritual warfare, in prayer, in practical caring, sometimes in protest and political action, always in the faithful teaching of the biblical message. Also in upright and holy living, as Peter says “the pledge of a clear conscience towards God” (NIV); “the appeal to God for a good conscience” (ESV). As we look towards Easter, we rejoice in the implications of the cross and the resurrection for us and our church family, and also for the world, for what is seen and unseen, as we cry out to God “thy kingdom come”.

See also:

How can we trust God when bad things happen? by Martin Davie, Christian Today

Bishops crossing the Tiber: What is the church?

By Andrew Symes, Anglican Mainstream:

When Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali announced that he was leaving Anglicanism to join the Roman Catholic Church in September last year, it was a bombshell that even those who thought they were close to him on the Anglican and wider Protestant side were not expecting. Many felt it was a betrayal. Some took to social media to express strong criticism of the move, reopening hostilities about Roman Catholic theology; others, for example Gafcon leaders, communicated their profound disappointment privately.

I felt that the approach taken by Gafcon Great Britain and Europe was the right one at the time. Michael had made the decision and already “crossed the Tiber” without any hint of discussion with anyone apart from those in his new fellowship. He was not going to be persuaded to change his mind; attacking him personally was not going to achieve anything. The best thing to do was to express appreciation for what he had done for the cause of biblically faithful Anglicanism, affirm that his analysis of Western secularism and revisionist Anglicanism is largely correct, but re-commit to the ideals and vision of a renewed Anglicanism through Gafcon.

But Michael’s recently published, substantial essay, published in First Things, setting out his reasons for going to Rome, perhaps calls for a fresh response. It’s a bit of a risk to do this, as I don’t claim to be Michael’s peer in experience, breadth of knowledge, or theological and cultural understanding, and I don’t want to jeopardise the relationship we have. However, I think it is worth asking some questions “from below”, as someone who has great sympathy with his decision to leave institutional Anglicanism but like many people on the ground, does not agree with his ecclesial destination.

Michael recounts a growing frustration during his years on official Anglican and Catholic dialogue initiatives. There was, he believed, increasing convergence on some doctrinal issues in the dialogues, but moves towards unity were shattered many times by “unilateral and unprincipled action” by Anglicans. He mentions the ordination of women, and then of ordination of those in active homosexual relationships. Where is the authority holding churches to a standard? Where is the “apostolic continuity”? What has happened to the commitment to greater unity between the denominations? These are fair questions about process (leaving aside the theology behind his opposition to women’s ordination, which many orthodox believers would say is of a different order to that of sexual morality).

There is also an accusation of “saying different things to different partners”, with Anglican negotiators coming up with different language and content for working with Catholics and other European protestants; a failure to balance local autonomy and subsidiarity within the Anglican Communion with any kind of discipline over innovations in doctrine and ethics, a “tendency…to capitulate to the culture rather than sound a prophetic voice within it”. While the gospel needs to be communicated afresh in different cultures, and while new insights can come from this process, Anglicans have gone too far in permitting “syncretism” – allowing culture to change the gospel message as to make it unrecognisable. By contrast, Michael says, Roman Catholics have an “authentic teaching authority”, made up ultimately of the Pope and the bishops, which acts as a bulwark protecting faithfulness to Scripture, and which avoids doubt over what the church teaches.

Protestants have an inadequate view of the sacraments, Michael goes on to say. He asks repeatedly “why not” give the designation of ‘sacrament’ to other important aspects of the church’s life (he mentions ordination and marriage as examples, but does not talk about penance…) He uses most the rest of his article to address other key theological issues such as Scripture, justification by faith, “real presence of Christ” in the Eucharist, the saints, the Virgin Mary, and prayers for the dead. In each case with customary careful and concise language he explains why he thinks former Protestant understandings are compatible with, and enhanced by his acceptance of Catholic teaching. He ends by commending the Ordinariate as a kind of “best of both worlds”, where he retains some Anglican tradition while being under the authority of Rome.

It’s probably not fair to accuse Michael of glossing over some centuries-old divisions in an article with such broad scope and a tight word count, although the foundational theological problems in institutional Roman Catholicism highlighted by the Reformation have not gone away. I hope that others more qualified than me will address some of these areas in detail. But I would like to express some broader questions, by pointing out some gaps in his account.

First, given that Michael clearly has had doubts about Anglicanism and sympathies with the Roman Catholic expression and its institution for many years, why did he not make the move earlier? Such a major shift of allegiance cannot be just intellectual or even spiritual. It would be interesting to know more about relational factors – who was he talking to? Was there a group which drew him in? Might this point to a failure – not theological but relational – in the orthodox Anglican world, particularly in England?

Then, within orthodox Anglicanism globally, important voices have for some time been calling for something similar to what Michael says is needed: a new ‘conciliar’ approach to the development of an authentically Anglican global body committed to orthodoxy; more than just a movement of like-minded people and churches committed to mission, but an authoritative ‘centre’ made up of representatives from the whole church, guaranteeing alignment with the apostolic faith.

Michael was in a unique position, given the high esteem with which he was held in England and globally with Gafcon and wider, to provide exactly the kind of leadership for a global orthodox Anglican conciliarism he felt was lacking. But when people looked to him for this, he was curiously diffident. Was this because he felt unfit for the task, or – perhaps because of the inner conviction about his ultimate destination with Rome which he was holding for some time?

The answer to the problems with liberal Anglicanism which he outlines surely lie in a new reformation and renewal of Anglicanism, rather than its abandonment. Michael doesn’t mention attempts to do this, for example the John Stott-inspired heritage of diverse but united evangelicalism standing firm for biblical truth within the Church of England. Nor does the global Gafcon project feature, part of a wider ‘Global South’ movement in which he had played a leading role for many years, including being the President of the Great Britain and Europe Gafcon branch, and overseeing the establishment of the Anglican Network in Europe as a new Anglican jurisdiction committed to orthodoxy. Clearly Michael was disappointed in what he felt was elements of compromise, and lack of institutional ecclesial strength in these movements, but it is a pity when discussing Anglicanism as he does in his article, only to reference the official, Canterbury-aligned structures, and not to see any hope in the vibrant orthodox grass roots of Anglicanism globally.

And it is ultimately at the grassroots where authentic Christianity stands or falls, not in the eminence of its leaders and the impressiveness or weaknesses of its institutions.

In Isaiah 8, the context is the Kingdom of Judah, trembling with fear as it is threatened with attack from its northern neighbours, Israel and Syria. Yahweh, through the prophet, says that these small nations will soon themselves be swallowed up by a much bigger threat, Assyria. The tendency of God’s people is to panic at the latest disruption, and to put trust in political alliances, and worse, returning secretly to the worship of the old gods to bring security. Instead,

“Do not fear what they fear… The Lord almighty is the one you are to regard as holy, He is the one you are to fear…

He will be a holy place; for both Israel and Judah he will be a stone that causes people to stumble, and a rock that makes them fall.”

Isaiah 8:12-14

Rather than urging a rallying to the visible political and religious institutions of Judah, the prophet says:

“I will wait for the LORD, who is hiding his face from the descendants of Jacob. I will put my trust in him.

Here am I, and the children the LORD has given me. We are the signs and symbols in Israel from the LORD Almighty, who dwells on Mount Zion.” (v17-18).

Certainly Michael Nazir-Ali has seen more clearly than most the way that Christianity is threatened, historically by overt persecution in the East and South, and more recently and insidiously, by the ideological takeover of secularism in the West. Not to mention the recent additional challenges of pandemic, war and economic squeeze. Of course I am not saying that he is not personally looking to the Lord for salvation, or that he believes returning to the “true church” is somehow a substitute for deep individual repentance and cleaving to the Lord which we all need to do. But it does seem from his apologia in First Things that he thinks the Roman Catholic church is an ark which will guarantee protection from the error, compromise and apostasy seen in Anglicanism and other established Protestant denominations.

But can any institution provide this? The message from Isaiah, reinforced in the gospels and the rest of the New Testament, seems to be that the main ‘unit’ of believing, living out and witnessing to authentic faith in Christ is not something visible and apparently strong, like a nation or a religious institution, but a local community, often unremarkable and unprestigious. It is the ‘children’ who are the signs and symbols of Yahweh, just as Jesus spoke of the meek “little ones” who see the Father’s face (Matt 18:10), and Paul spoke of the church in Ephesus, probably just a few small groups of families, as the household of God, the new temple, the spiritual beacon of God’s wisdom. (Ephesians 2:19-21; 3:10). Good structures are important, but it is the cross, the Holy Spirit, the Word, and ordinary people of faith in Christ which makes the church and defines and protects orthodoxy.

I hope that as Michael embarks on his new journey in the Roman Catholic church, he will experience the joy of being part of a small, faithful community, and see that it is in networks of these gospel cells that the apostolic faith is preserved, not necessarily in the high offices, pronouncements and religious rituals of Popes, bishops and Synods in their gilded buildings.

Bishop sides with Pride against orthodox clergy

By Andrew Symes, Anglican Mainstream:

In the middle of the street in the centre of Oxford, a small cross made of cobblestones marks the spot where Anglican leaders were tortured and killed for following their conscience and refusing to submit to laws which conflicted with their biblically-informed faith. As Bishops Latimer and Ridley, and Archbishop Cranmer burned, fellow clergy and former colleagues watched and approved, as Saul did at the stoning of Stephen.

The love of acceptance by the establishment, the need for power, the fear of being on the ‘losing’ side, have caused Christians in every age to keep quiet or even approve while their brothers and sisters suffer for Christ. In many cases, they have convinced themselves that conforming and adapting their own faith to the demands of the ruling ideology, and attempting to eradicate authentic Christianity, is a good thing, perhaps for the stability of the nation, or for the sake of “justice” according to the new definition of the governing elites.

I’ve been reflecting on this as a historical scene-setter to the intervention by Gavin Collins, Bishop of Dorchester, Suffragan of Oxford Diocese, in response to the naming on social media by Oxford Pride of those Oxford clergy and laity who signed the ‘Ministers’ Consultation Letter’ calling on the government to re-think plans to introduce a ban on ‘conversion therapy’. The key documents are here:

Minister’s Consultation Letter opposing ‘conversion therapy’ ban

BBC report: Oxford Pride condemns conversion therapy open letter

Statement by Bishop Gavin Collins on the Diocese of Oxford website

In his statement, the Bishop makes several remarks which are incomprehensible without detailed knowledge of the background. They operate as slogans or tropes, signalling which side he is on rather than bringing wisdom and clarity. He does not address the actual concerns expressed in the letter which has been signed by some of his own clergy, for example that the government’s reasoning for the ban conflates already-illegal coercive and violent attempts to suppress homosexuality with looser definitions which end up including freely chosen counselling and prayer, and any perceived criticism of LGBT ideology or promotion of heteronormativity. He does not explain why a letter expressing concerns about retentions of basic freedoms should cause “people” (presumably, LGBT people?) to feel “upset” and not “safe or welcome in our churches”.

The Bishop goes on to say that the motive of the authors of the letter is to “diminish people” with certain identities and lifestyles. Since the purpose of the letter is to point out the need to retain freedom to practice Christian teaching and pastoral care relating to sexuality, and the Church of England officially agrees with that teaching, does this mean that Gavin Collins believes the doctrines and canons of the church of which he is a bishop inherently diminish people?

He ends with what could be seen as a summary of his ‘gospel’ message in three points: all are made in God’s image, all are welcome in church, everyone has a place at the table. What does he mean? Is he only saying, for example, that a Muslim or atheist should be warmly welcomed in a church service? Or is he going further – that they should receive the sacraments without discrimination? That they are members of God’s kingdom by virtue of their common humanity? The Bishop clearly has in mind all three interpretations. Again, some background is needed here: the Bishop is being consistent with the move towards “radical inclusion” outlined in the letter by Diocesan Bishops to clergy in October 2018:

Text of 2018 Ad Clerum: “Clothe yourselves in Love”

Anglican Mainstream commentary: “This interpretation of the full inclusion of LGBTI+ people in the church, then, is not simply about love of neighbour, and welcoming those who are different. It involves a radical change in Christian anthropology and sexual ethics.”

Oxford Diocesan Evangelical Fellowship’s letter protesting against the Ad Clerum

The timing of the Bishop’s intervention is also significant, coming immediately after Oxford Pride published the names of clergy and laity from Oxford churches who had signed the letter, one of which was myself. Gavin Collins is signalling that he, and the Church of England leadership whose Synod voted for a ban on conversion therapy in 2017, are on the side of Pride against their fellow Anglicans. He no doubt sincerely believes that in doing so he is on the side of the oppressed against the powerful, but in reality it is the opposite, as he is aligning with the might of government, the media and the corporate world against those who dare to say that sexual desire does not define identity, and that God calls us all to repentance and conformity to his standards .

Collins is joining other bishops (eg the Bishop of Manchester) in saying he would support the future criminalisation of his own clergy if convicted of ‘conversion therapy’, perhaps if they teach the biblical view of marriage, or by counselling someone who wants to manage same sex desires in a faith-directed way, or leave LGBT identity and lifestyle. We are in a different era – they don’t burn people at the stake nowadays – but there is a parallel between the craven senior clergy who watched approvingly at the demise of the Oxford martyrs, and Bishops today who support laws banning their own clergy from fulfilling aspects of their ordination vows.