What are the main problems with contemporary secular culture, and why?

By Andrew Symes, Anglican Mainstream:

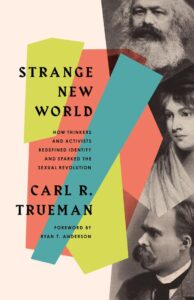

“In late 2020, while the world was on lockdown due to Covid-19, Carl Trueman published one of the most important books of the past several decades”. So begins Ryan Anderson in his foreword to Trueman’s latest book, “Strange New World: How thinkers and activists redefined identity and sparked the sexual revolution” (Crossway). While Anderson might be guilty of slight hyperbole, it’s certainly true that Trueman’s 2020 tome “The rise and triumph of the modern self” was very quickly seen as extremely important by conservatives seeking to understand the massive recent changes in the culture and worldview of the West. My feeling when reading Trueman was overwhelmingly one of relief – that at last someone was articulating soberly and clearly what the problem is. It wasn’t so much that it was new to me, but that his thesis confirmed and put together the fragments of ideas that I and others have been struggling to explain as we surveyed and chronicled the essential ideas of ‘progressivism’ or ‘woke’, and how they impact society and the church.

“Strange New World” (SNW) is not a summary of “Rise and Triumph”, but a more concise and accessible re-statement of the same main points:

- In the contemporary West, there has been a rapid and disruptive shift in how we see ourselves as human beings.

- The understanding of the self has moved from a subject-object, being an individual but existing within the constraints of a divinely-ordered creation and of community obligation, to a pure subject, in which my own feelings and desires define my identity and purpose; community rules and even biology can be seen as constraints on the authentic self.

- The self does not find authenticity in conforming, but in performing. So we have a culture of “expressive individualism”, which “holds that each person has a unique core of feeling and intuition that should unfold or be expressed if individuality is to be realised”, so therefore “authenticity is achieved by acting outwardly in accordance with one’s inward feelings” (SNW p22-23).

- The most obvious application of this is the sexual revolution. This is not simply a loosening of boundaries of sexual morality. It is seeing the self as largely defined by sexual preference and gender identity, so that the old moral boundaries are an existential threat to the expression of the newly liberated self.

- These new ideas did not suddenly emerge recently, but have been cooking for decades, even centuries, as Western culture has moved away from its Christian roots to a secular worldview. Delving into the history of the key ideas which have shaped this revolution helps us to understand more clearly what is happening, and what can be done about it by those who see the trajectory as hostile to Christian faith and destructive of human flourishing.

- So, having a basic grasp of the philosophies of Rousseau, Nietzsche, Marx, Freud and Reich is not just of academic interest. It sheds light on the assumptions of the majority in contemporary society in which we live, in relation to the nature of reality and the individual, how society should be run, where power resides, the combination of sexuality and politics in driving revolutionary change.

- Expressive individualism and Marxism have combined in a toxic mix, so that “two of the most unquestioned freedoms of Western liberal democracy, those of speech and religion, are now in serious jeopardy” (SNW p147). Anything which perpetuates the normativity of the old order must be suppressed and eliminated; this includes, of course, conservative Christianity.

- We are in a strange new world. “The last vestiges of a social imaginary shaped by Christianity are vanishing” (p169). Churches have been complicit in adapting theology and practice to the new thinking, rather than go through the costly process of critiquing it from a biblical perspective.

- The contemporary church needs to follow the example of the early church. Not by “warfare using the world’s rhetoric and weapons” (p177), but also not by being “passive quietists”, simply repeating messages that answer the questions of previous generations. Rather, recognising the spiritual battle, the church develops consciously Christian counter-culture of message, worship and community, offering an alternative, true vision of what it means to be human.

- “This is not a time for hopeless despair or naïve optimism. Yes, let us lament the ravages of the fall as they play out in the distinctive ways our generation has chosen. But let [this lead to] sharpening our identity as the people of God…” (p187).

All this in 200 pages means that Trueman’s new book is excellent, accessible to a wider audience than the much longer work, and a vital addition to the growing library on Christianity and culture, alongside, for example, Melvin Tinker and Sharon James. There is still a challenge for popular communicators to translate Trueman’s material into bite-sized chunks on video, and perhaps for churches and networks to incorporate some of its key insights into teaching material and statements of faith.

Other recent reviews can be read here:

How the self transformed sex, by Shane Morris, The Gospel Coalition

The best historical explanation of our current cultural crisis, by Jim Denison, DenisonForum

Strange New World, by Tim Challies

What are some of the immediate implications for Anglicanism? Trueman has shown that the problems of the 1970’s and 1980’s – growing acceptance of previously taboo sexual behaviours by radicals within the church, has become something different: the elevation and aggressive politicisation of the ‘authentic self’ based on ‘lived experience’, particularly sex and gender identity. This agenda has been supported by bishops and the church institutions in the West (for example, much of the text and video material in Living in Love and Faith assumes it), while evangelical and other orthodox leaders have often failed to sufficiently identify, analyse and resist it.

Those who accept Trueman’s thesis can be guilty of being over-pessimistic about the possibility of preserving a strong authentic Christian witness which can influence and change culture for the better, or perhaps too quick to withdraw from cultural engagement altogether. Others see the solution in tying church support too closely to partisan political leaders and programmes. But there are many Christians who, while retaining faith in bible-based doctrine and ethics, are not aware how much their thinking and practice has been shaped by secular thinking.

As Gavin Ashenden has recently pointed out, it has taken the courage of secular ‘prophets’ (he mentions Jordan Peterson and Douglas Murray) to raise the alarm, and to cause some church leaders to wake up and listen, when previously they were not paying attention to those in their own flock who have been making the same warnings for years. It may be that Carl Trueman’s books would have remained largely unread and unnoticed in the UK, were it not for high profile people outside the church (more: JK Rowling, The Times newspaper, Rod Liddle, Brendan O’Neill of Spiked, Kathleen Stock…) essentially saying we are entering an Orwellian dystopia: “this is not a drill”.

See also:

Lessons for the Church from the current transgender debate, by Jeremy Dover, Christian Today:

…our current cultural position of accepting “I am a woman trapped in a man’s body” is not the problem but just the symptom. Trueman says the true root of the issue is a “deeper revolution in what it means to be a self”.

Is “Be True to Yourself” Good Advice? by: Brian S. Rosner, Crossway

You don’t need to look far today to notice that personal identity is a do-it-yourself project.